Do Jellyfish Swim In Groups

Introduction

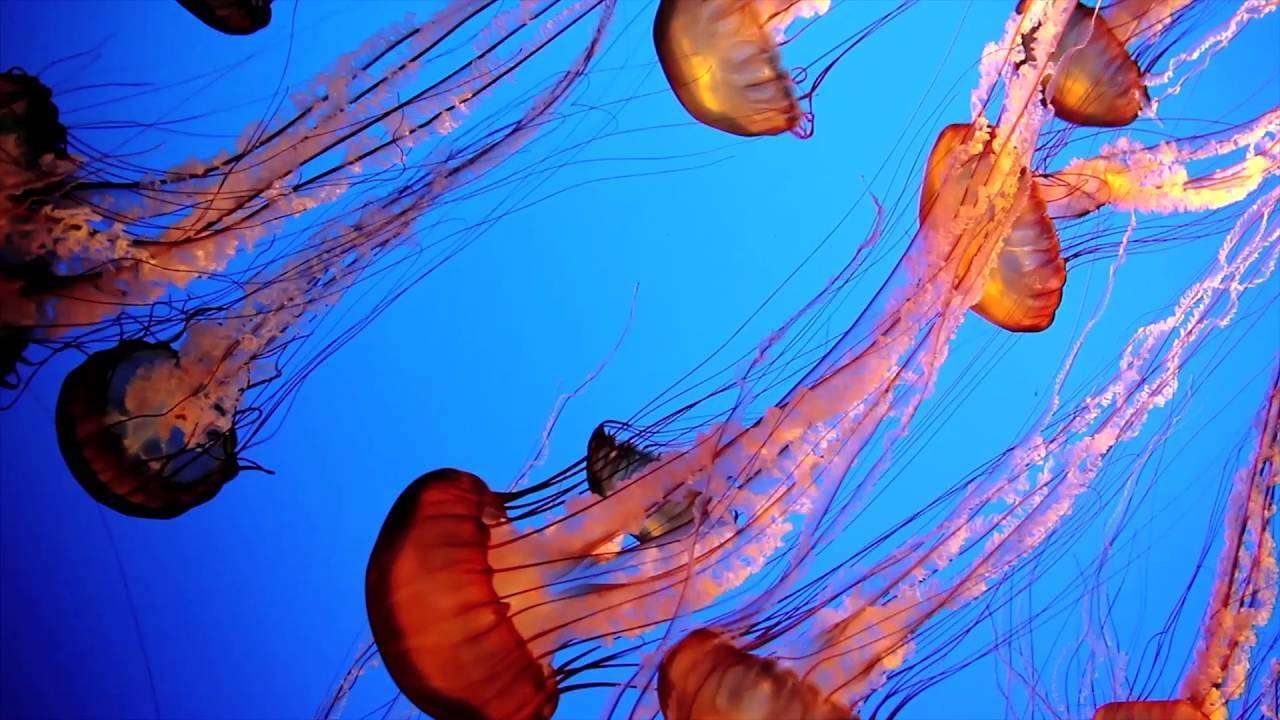

Do Jellyfish Swim In Groups: Jellyfish, those captivating and enigmatic denizens of the deep sea, have long intrigued scientists and ocean enthusiasts alike. These gelatinous creatures, known for their graceful, otherworldly movements, are often solitary drifters in the vast expanse of the ocean. However, the question of whether jellyfish swim in groups has garnered scientific interest and sparked curiosity among those who study marine life.

The notion of jellyfish swimming in groups challenges the common perception of these solitary drifters. Typically, jellyfish are thought to glide through the water solo, carried along by ocean currents, seemingly oblivious to one another.

Recent research has revealed that these seemingly solitary creatures occasionally engage in a coordinated, synchronized dance. Understanding the dynamics of group swimming in jellyfish not only sheds light on their mysterious lives but also provides valuable insights into the broader field of marine biology.

We delve into the intriguing world of jellyfish potential for social swimming. We will uncover the reasons behind this behavior, the mechanisms that underpin it, and the implications it may have for our understanding of ocean ecosystems and biodiversity.

Do jellyfish live in group?

With their huge number of venomous stinging cells, jellyfish aren’t very cuddly. A few have been observed engaging in social feeding behavior , but for the most part, they’re loners. However, jellyfish do have families, just like everyone else.

Jellyfish are predominantly solitary creatures, known for their solitary drifting in the vast expanses of the ocean. They move with the currents, seemingly oblivious to one another. However, there are exceptions to this solo lifestyle. While jellyfish are not inherently social animals, some species do exhibit group behavior under specific circumstances. When environmental conditions are favorable, and resources are abundant, jellyfish may come together in loosely organized aggregations.

These groups are not as tightly knit as those of schooling fish, for example, but they do engage in coordinated, synchronized swimming patterns. The reasons behind this group behavior are diverse and often tied to survival. Grouping can provide advantages like increased protection from predators and enhanced efficiency in finding food.

Such social gatherings are not a permanent or strict arrangement and may disband as environmental conditions change. The study of these jellyfish group dynamics is essential in unraveling the intricacies of marine life and contributes to our broader understanding of ocean ecosystems. It underscores the adaptability and resourcefulness of even the simplest organisms in response to their surroundings.

Why do jellyfish swim together?

Though jellyfish are often found in dense, stinging hordes, they’re not typically thought of as social animals. These blooms, or “smacks,” actually have more to do with converging water currents than any sort of intentional schooling behavior.

Jellyfish, typically solitary drifters in the open ocean, occasionally exhibit the intriguing behavior of swimming together in groups. This phenomenon, while not common to all jellyfish species, raises questions about the reasons behind this behavior. Several factors drive jellyfish to form aggregations, and they revolve around the fundamental principles of survival and adaptation.

One of the primary motivations for jellyfish to swim together is the pursuit of food. In areas where prey is abundant, such as dense plankton blooms, jellyfish can benefit from the collective efforts of a group. Swimming in unison, they can concentrate and corral their food source, making for more efficient foraging. This cooperative behavior allows them to optimize their feeding and energy acquisition.

Protection from predators is another compelling reason for group swimming. Safety in numbers is a strategy employed by many organisms, and jellyfish are no exception. The presence of multiple individuals can deter potential predators, making it less likely for any single jellyfish to fall victim to an attacker. The combined presence of stinging tentacles from multiple individuals in the group can also create a formidable defense against would-be threats.

Overall, the phenomenon of jellyfish swimming together underscores their adaptability and resourcefulness in the ever-changing world of the ocean. Whether driven by the pursuit of sustenance or the need for safety, this behavior provides a window into the fascinating strategies employed by even the simplest of marine organisms to thrive in their underwater realm.

Do jellyfish travel in pairs?

They Rarely Travel in Groups

Many refer to a group of jellyfish as a bloom or a swarm, but they can also be called a “smack.” In any case, seeing a group of jellyfish is rare considering these animals are mostly lone drifters.

Jellyfish, as a general rule, are not known to travel in pairs. They are primarily solitary creatures that drift through the oceans alone, carried by ocean currents. Their solitary lifestyle is characteristic of most jellyfish species.

However, there are occasional exceptions where you might find two jellyfish in close proximity, but these instances are usually not indicative of a social or pair-bonding behavior. Instead, they could be brought together by environmental factors, such as ocean currents or concentrations of prey.

Jellyfish are highly sensitive to changes in their environment, and while they do not typically form permanent pairs or social groups, they might come together temporarily in situations where conditions are favorable for feeding or reproduction. During breeding seasons, for instance, male and female jellyfish may interact to release and fertilize eggs, but these interactions are brief and not indicative of long-term partnerships.

While you might occasionally come across two jellyfish swimming together, it’s usually due to transient circumstances or environmental factors rather than deliberate social behavior or long-term pairing. The solitary nature of jellyfish remains one of their defining features in the world of marine biology.

How many jellyfish travel together?

A group of jellyfish — which can include up to 300,000 of them — is called a bloom, a swarm or a smack.

The number of jellyfish traveling together can vary widely depending on several factors, including the species of jellyfish, environmental conditions, and specific circumstances. Jellyfish are typically solitary creatures, known for drifting alone through the open ocean. However, there are instances where they may come together in small groups or aggregations.

In some cases, you might find just a few individuals swimming in close proximity to one another. These gatherings are often driven by favorable conditions for feeding, such as the presence of abundant prey. In these scenarios, a small group of jellyfish can work together to concentrate and capture their food more efficiently.

On the other hand, certain species of jellyfish are known to form larger aggregations, sometimes consisting of hundreds or even thousands of individuals. These aggregations are often seen during breeding events when male and female jellyfish come together to release and fertilize eggs. These aggregations can also occur in response to changing environmental conditions, including variations in water temperature, salinity, and food availability.

The number of jellyfish traveling together can range from just a couple of individuals to massive gatherings, depending on the species and the specific ecological context. Their ability to adapt and respond to their surroundings is a testament to the flexibility and resilience of these fascinating marine creatures.

How fast does a jellyfish swim?

About two centimeters per second

Typically, jellyfish swim at a rate of about two centimeters per second. Although they are capable of moving more quickly, doing so does not aid them in ensnaring prey, their typical reason for using the tentacle-waving “swimming” motion.

Jellyfish are not known for their speed or efficient propulsion. Their method of movement is primarily reliant on pulsations of their bell-shaped bodies, which expel water and propel them forward. On average, most jellyfish move at a leisurely pace of about 2-6 inches (5-15 centimeters) per second. However, some species can attain slightly higher speeds. For instance, the lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) can achieve a modest speed of up to 2 feet (60 centimeters) per minute, propelled by the rhythmic contractions of their bell.

The swimming speed of a jellyfish is influenced by various factors, including its size, species, and environmental conditions. Larger jellyfish may have more water to expel, allowing for potentially faster movement. Additionally, water temperature and salinity can affect their buoyancy and thus their ability to navigate through the water.

In comparison to many other marine creatures, jellyfish are considered slow swimmers. Their deliberate, pulsating motion is well-suited for their lifestyle as passive drifters, allowing them to efficiently capture planktonic prey and navigate ocean currents in search of food and suitable habitats.

What types of jellyfish are known to swim in groups?

Various species of jellyfish are known to exhibit group behavior, a phenomenon that is not universal across all jellyfish but is observed in certain taxa. One notable example is the “Aurelia aurita,” commonly known as the moon jellyfish. These translucent creatures are often found in aggregations, particularly in coastal and estuarine environments. They engage in a diurnal vertical migration, moving up towards the surface at night to feed on plankton and descending to deeper waters during the day for protection.

The lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) is another species known to congregate in groups. With its distinctive trailing tentacles, this species can form dense swarms in cold, northern Atlantic waters. These aggregations are influenced by factors such as water temperature, salinity, and prey availability.

Certain box jellyfish species, such as Chironex fleckeri, have been observed swimming in loose groups, especially during their reproductive phases. These powerful and potentially lethal creatures are primarily found in the Indo-Pacific region.

While these are some prominent examples, it’s important to note that not all jellyfish species exhibit group behavior. The tendency to swim in groups can be influenced by ecological, environmental, and reproductive factors specific to each species, showcasing the diversity and complexity within the fascinating world of jellyfish biology.

How do jellyfish coordinate their movements in groups?

Jellyfish, despite their seemingly simple anatomy, exhibit a remarkable capacity for coordinated movement in groups. Their synchronicity arises from a combination of biological instincts and environmental cues. Central to this coordination is a specialized network of nerve cells called the “nerve net,” which spans their epidermis. While lacking a centralized brain, this nerve net allows for basic sensory perception and communication between cells.

Jellyfish possess specialized structures known as rhopalia, which house clusters of nerve cells and sensory organs. These rhopalia act as localized processing centers, enabling individual jellyfish to respond to stimuli and make localized decisions. In a group, these decisions are communicated through a complex interplay of biochemical signals.

Environmental factors, such as water currents, light levels, and chemical gradients, also play pivotal roles. Jellyfish possess specialized structures, like statocysts, which sense changes in gravity and orientation. This information, combined with photoreceptors that detect light, enables them to orient themselves within their surroundings.

Hydrodynamic interactions among neighboring jellyfish contribute to group cohesion. By modulating the pulsing rhythm of their bell-shaped bodies, jellyfish can adjust their propulsion and direction. This allows them to synchronize movements, creating mesmerizing displays of undulating, ethereal ballets.

Overall, jellyfish exhibit a sophisticated blend of biological predispositions and environmental responsiveness that enable them to coordinate their movements within a group, showcasing nature’s intricate adaptability.

Are there any dangers associated with swimming near groups of jellyfish?

Swimming near groups of jellyfish can pose significant dangers to individuals. While not all jellyfish species are harmful, many possess stinging tentacles equipped with venom designed to incapacitate prey. When humans come into contact with these tentacles, they can experience painful stings, which may lead to skin irritation, redness, and in severe cases, allergic reactions. Some species, such as the box jellyfish, harbor venom that can cause cardiovascular issues and, in rare instances, even be fatal.

Swimming amidst a group of jellyfish increases the likelihood of accidental encounters, as their translucent bodies can be difficult to spot, especially in murky waters. Even after their demise, detached tentacles can retain their stinging capability, posing a threat to unsuspecting swimmers.

In regions where jellyfish blooms are common, local authorities often issue warnings and implement safety measures, such as nets or vinegar stations, to mitigate the risks. It is crucial for swimmers to heed these advisories and exercise caution when entering waters known to harbor jellyfish. Additionally, wearing protective clothing, such as rash guards or stinger suits, can provide an extra layer of defense against potential stings. Overall, understanding the risks associated with swimming near jellyfish is essential for ensuring a safe and enjoyable aquatic experience.

Conclusion

Whether jellyfish swim in groups has illuminated the fascinating complexities of marine life. While these ethereal creatures are often perceived as solitary drifters, recent research has unveiled instances of coordinated group swimming among them.

The reasons behind this behavior appear multifaceted. Environmental factors, such as food availability and ocean currents, seem to play a role in driving jellyfish to form groups. Moreover, the advantages of group swimming include enhanced protection from predators and improved foraging efficiency, turning the seemingly solitary jellyfish into cooperative foragers.

This newfound understanding not only deepens our appreciation for the intricacies of marine life but also highlights the delicate balance that exists within ocean ecosystems. It underscores the importance of preserving these environments, recognizing that the behaviors of even the most enigmatic creatures like jellyfish contribute to the overall health and stability of the oceans.

The study of jellyfish group behavior holds promise for broader applications, from informing the management of fisheries to enhancing our grasp of the dynamics of marine ecosystems. In this context, unraveling the mysteries of jellyfish group swimming exemplifies the exciting potential of marine science to reveal hidden facets of the natural world and how they impact the delicate web of life beneath the waves.